- Home

- S. E. Craythorne

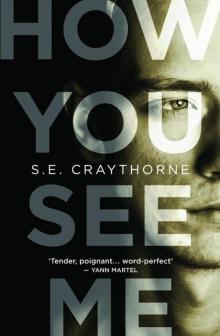

How You See Me

How You See Me Read online

Praise for How You See Me

Shortlisted WRITER’S RETREAT COMPETITION

Longlisted MSLEXIA WOMEN’S NOVEL COMPETITION

‘A tender, poignant story, deftly executed and written in graceful, word-perfect prose. Whoever said the novel was dead hasn’t read S.E. Craythorne’s How You See Me. She revives an old conceit – the epistolary novel – while making a modern point: how very hard it is to know ourselves, and so how very hard it is to be understood by others. This is Romeo and Juliet meets Camus’ L’Etranger. When I finished the book, it left me gutted, really gutted.’

Yann Martel

‘In this dark, intoxicating novel, S.E. Craythorne writes about being loved and being lost. The style is understated and highly effective, the characters vivid and true, and the story compelling. It’s a wonderful, devastating read.’

Alice Kuipers

‘Craythorne draws – with a very, very sharp pencil – a painfully acute portrait of a damaged inner life. In spare, expertly controlled prose she slowly reveals, through fragments and letters, a tale which is genuinely chilling: it achieves that rare thing of leaving the reader physically affected. It has a kind of willingness to face the grotesque with intelligence and wisdom that calls to mind the dark novels of Anne Fine or Lesley Glaister – a fine debut all the more striking for being so absolutely assured in its use of form.’

Sarah Perry

Contents

Praise for How You See Me

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

How You See Me

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

For Mum, Heidi and John

‘Everyone is the hero of their own story.’

Hayley Webster, Jar Baby

10th September 2005

Manchester

Dear Mab –

I tried to phone the hospital, but the ward sister couldn’t track you down. This should arrive just before me. I’m on my way, so don’t – either of you – go anywhere. If Dad gets moved or anything just leave word at the desk – or whatever they have – and I’ll find you. Do the same if he gets any better and decides not to see me.

I phoned the ‘charlatan’ (I told Aubrey you call him that, by the way). He’s given me time off work to visit Dad. He said that, on consulting his notes, I appeared to have all the tools I needed to watch my father die. Perhaps we could replace ‘charlatan’ with ‘arsehole’? I held my temper by imagining your response. Still, I’m coming.

I’m probably pulling into the car park now. Find a window and wave.

Daniel

From the pillow next to yours

Dear Alice –

You are sleeping while I write this.

You were sleeping when I opened the letter from my sister. I picked up the post from my flat on my way here tonight. My father is very ill and I have to leave right away. You’ll say I should have woken you, but there’s too much to say. Too much I haven’t said. A father and a sister. A whole life to explain. I’m sorry I’ve not told you about any of this before; we’ve had so little time together. I’ve probably lied to you. That’s habit. I lie to everyone about my family.

You are the only person I have ever seen sleep fiercely. Aren’t we meant to look our most innocent when we sleep? Like little children. You look as though you’re defending something. Your hands are curled into fists and you’re frowning, as if you’re ready to fight. But your lips are soft.

You were sleeping when I kissed you goodbye.

I’m not sure how long I’ll be gone. I’ll write when I know what’s happening. I wish I could stay. I wish I could gather you up and take you with me. My sleeping warrior. You’d make an excellent talisman. I think I might need one.

Missing you already, my darling,

Your Daniel

12th September

Dad’s hospital bed

Dear Mab –

What you didn’t have to do was run out on me! I only saw you for two minutes, and you disappeared. I am here. I turned up, just like I said I would. I didn’t want to be here, but I was ready to do – I was already doing – anything you wanted me to do. And you vanish!

To tell you the truth – and what point is there in telling you anything else? – I’m so angry I can barely write. And I’m writing, for Christ’s sake! With a pen! No number! Not even an email address! Who leaves a PO Box address for their own brother?

I hope this scrawl reaches you. If I could find the tools, I would have cut the words into the page. But, instead, I borrowed a pen from the nurse and was told not to damage it. Observant, these nurses – I must look murderous. Get back here, before they have me arrested!

I’m not the person to do this, Mab. Please don’t make me.

Daniel

PS Eleven down was jug.

13th September

Hospital

Dear Alice –

Yesterday, I met my sister for the first time in nine years. Actually I met her feet. They were crossed, propped up on my father’s hospital bed. She was wearing a pair of those knitted slipper socks they ship over from Tibet or somewhere like that, leather soles clumsily stitched to the feet. I could see the imprint of each toe on those dirty leather soles and a well-trodden sticky patch of what looked like gum. She looked up from her crossword and smirked.

‘You look as if you’re waiting to be announced.’

Her daughter, Freya, wasn’t with her and Mab avoided my questions about her. I would have sat in the chair next to her but she moved her feet over from the bed and started up some yogic stretching. I sat on the edge of Dad’s bed to watch her. I had to shift his legs; they felt like nothing more than fallen branches.

Mab’s looking old. She’s only thirty-four, yet there are wrinkles and grey hairs and even glasses on a ribbon round her neck. She caught me staring. ‘Watching my wickedness catch up with me?’ She gathered up a pile of jumpers and scarves from her chair – more woollens. ‘I can’t make anything of eleven down; do what you can. I need coffee.’

She brushed my hair and Dad’s arm with the same gesture and left. That was last night; I’m still waiting for her to come back.

I wish I were writing you love letters, instead of all this garbage about my family. I wish I could call you, but I think if I heard your voice I’d run home right now. Are you seeing Aubrey? I know your session is booked for today. It’s usually the highlight of my week. I hate to think of you sitting in that office. I hate to think any of it can exist without me there to witness it.

Your Daniel xx

PS And she lied about the crossword. Even Mab could have got the Keats reference.

15th September

The Private Suite

Dear Mab –

Thank you for the cheque and for the letter. And for calming me down – you always were the only one who could do that. I do understand. But this has to be temporary. I have a life now and I like it. I can’t be here when Dad gets back to himself. We both know what he thinks of me then.

He’s much the same for now, but they’ve moved us into a side room. We have four walls of our very own! I don’t know if this is due to Dad’s snoring, or the nurses trying to hide the fact that I’m squatting in the hospital.

They were very sweet about ignoring the visiting hours at first, but when it became clear that Dad wasn’t going anywhere they started dropping hints about me leaving. I had the ‘freshen up’ and the ‘go and get some proper sleep’ lines dropped on me, quickly followed by my presence being described as ‘inappropriate’ and ‘against regulations’. But I have withstood them all and here I sit. They think I am either monumentally stupid or monumentally devoted. Or perhaps they’re planning to barrica

de the doors the next time I visit the cafeteria? But I just can’t face driving to the village or going back into the studio. It makes me feel sick. Probably best I stay here – at least there are plenty of doctors. Aubrey would approve.

Dad’s out of it most of the time, but I’ll be sitting next to his bed doing the crossword or reading a book and glance over to find him staring at me. I don’t think he knows me. He doesn’t look angry or horrified, just blank. There’s still no speech, but the doctor says that’s normal and to give him time. I wish they’d let me put his glasses on. I can’t remember if he used to sleep in them or not. He doesn’t seem right without his glasses on and a cigarette in the corner of his mouth. It’s like something’s been amputated from his face.

The nurse just now smiled at me as she came and went. They must have just given up on moving me. She asked me how far I’d come and, when I mentioned Manchester, said I’d brought the weather with me. The window was dark and catching splashes from the first of the rain. You don’t notice it in here. It’s like its own little world: sanitised, over-lit and overheated. I hope I managed a laugh at the nurse’s little joke. I need to stay on their good side. It is rather a horrible image, though, isn’t it? Me driving down here, towing a dark cloud behind me like some sinister kite.

Daniel

17th September

The Studio

Dear Alice –

I thought I hated this house, but being back in it is more confusing than hateful. There was no clichéd shiver down my spine or harp-accompanied wash of memories as I stepped over the threshold. Pathetically, I think that’s what I’d expected.

It’s a house; just a house. A long-abandoned stage set for my childhood memories. I just have to learn to tread the boards again.

That’s not to say there’s no familiarity. Everything is in its place. Let me give you the tour. From the front door you walk into the living room, with the wood-burner like a living eye in the wall. Beyond that are the kitchen and the bathroom, both with their naked concrete floors and windows overlooking the ragged garden. Upstairs, there is the studio, with the small cupboard bedroom to the side, which Dad used to sleep in before he moved downstairs. And tucked away in the attic is my childhood room and Mab’s. A simple house, that’s all it is. Yet running up the stairs, the smell of oils and turpentine, catching the wall as I turn into the kitchen, even fumbling for the lock on the bathroom door, is like a haunting. Only, I’m haunting myself.

Obviously last time I was here I was smaller, but I’ve always been awkward. I was too large for this house at fifteen. My feet were too loud on its floors; my shoulders banged against doorframes, my head against the beams. I was like your namesake after too much cake. All those long-healed bruises are ripening again.

One of my father’s models, Kirsty, was a dancer. She used to talk about muscle memory, working the dance into your bones. Like the characters of Mab’s masks that seem to stick to even the most sceptical actors. Have you ever seen mask work? It terrifies me.

I don’t want to be the person I left behind in this house. I don’t want to remember. I want to be with you, wrapped in your hair, your legs and your sheets. I want to fall asleep on your breasts, with my hands full of your flesh, my head full of your scent.

But whatever I want, like it or not, I’m home.

Your Daniel xx

19th September

The Studio

Dear Mab –

The first difficulty was getting Dad out of the car. It takes an age to rouse him to any action and I still haven’t learnt how to deal with him. I keep thinking of the nurses in the hospital:

‘Just pop your head up there, Michael.’

‘That’s the way, right foot; now the left. Nearly there, Michael, you’re doing nicely.’

Apparently the key is a soft and determined tone, as though you’re whispering to a fractious horse, and to use his name repeatedly, as if you’re in a bad radio play. Patronise, never be afraid to patronise. But that’s what I’m afraid of – ending up like Aubrey! I never thought I’d say it, but Dad’s been through enough without having his hulk of a son frisking him for his keys on the doorstep while muttering on and on about how ‘nearly there’ we are.

We were met by your letter, which was most welcome and gave me something to read in a normal voice after I’d got him into his chair.

I’d been back to the house briefly to check on things, but someone (I suspect Maggie – I could smell her in the Jeyes Fluid) had been in and done between times. There are cyclamen everywhere. I hate cyclamen. Half of them look near death and are just stubby corms cresting though the soil. Those flowers are too delicate; I always think I’m going to crush them. And the little tables she’d put them on – dragged from God knows where – have given me something else to walk into. Still, she’s sorted out milk and bread and everything else I’d forgotten. But it’s too clean in here; it looks shorn and pressed and not quite itself. Like poor Dad.

(Later)

I’d forgotten this house has a will of its own. I fired up the wood-burner, even though it’s so mild – Dad’s got used to hospital temperatures and kept shivering no matter how many pieces of clothing I pulled on to him. We were sitting peacefully drinking our umpteenth cup of tea – another hospital habit – and I started itching. The rug in the living room is alive with fleas! They’re everywhere. I’ll have to go into town and get something to blitz them.

Dad was restless until I switched on the TV. He seems to like the sound and the colours flashing over the screen. He still hasn’t got his glasses; they’re somewhere in the bags. I tried putting them on him before we left the hospital, but they looked too big for him – or his face looked too small, I don’t know.

I went outside and sat on the doorstep with a cigarette, picking black fleas off my ankles and cracking them between my thumbnails; examining my own blood. There is a row of roses that has been dug in along the side of the house, rattling with dead leaves. I jumped at a skittering around their roots (you know how I feel about rats – Winston Smith has nothing on me!) only to see a couple of brown birds appear. Tame, but interested. Perhaps someone’s been feeding them? Surely not Dad?

And, at the risk of confirming myself as the Great, Huge Bear returned home, someone’s been sleeping in my bed! I don’t mean it’s been made up; someone has just got out of it. The sheets pulled back and twisted and the shape of a woman curled and then removed. It smells of perfume. Her books are splayed and piled on the carpet, including a couple of Dad’s old sketchbooks, the gluey pats of oil paint stuck in the pile. I keep wondering who she is. My own personal Goldilocks!

Daniel

22nd September

Missing you!

Dear Alice –

You’re a pleasure to write to and somehow that pleasure is more real when I write than if I tried to call you. I imagine myself talking to you, and I can see just how you would listen: that hand scanning your face for blemishes which never exist, teasing out your hair, tugging and readjusting your clothes; your eyes anywhere but on my face. You worry about your appearance of restlessness, of a lack of interest, but it’s one of the things I love best about you. You are the one person who listens and understands. At least you try to understand.

Maggie came today. Maggie was an immense part of my childhood. Literally. Maggie was a tanker, a fatty, a blimp; she had two truck legs and a blubber butt; if Maggie jumped in, the water would jump out. This I learnt when I made the mistake of inviting a friend to tea. The next day at school was full of taunts. Charlie Gibson had told everyone about ‘that big fat woman with no knickers that cooked us eggs’. Until Mab put a stop to it. Maggie’s father was a butcher. His favourite boast was that he could feed three families with one slice off his daughter’s hind.

Maggie was, for a time, my father’s favourite model. She was certainly the one we loved best. Sturdy and oversized child that I was, it was my great ambition to be able to hug Maggie all the way round. Until then I had to love her

portion by portion, hanging off whatever giant limb or bulge came my way. She mothered me, I suppose. Poor motherless mite. She fed me and loved me and did her best.

She caught me at an awkward moment today. Dad was down for his mid-morning nap and I was missing you. There’s no internet here so – oh, I hope you’ll understand this! – I went to Dad’s studio and sorted through canvases searching for artistic pornography. You know my dad’s style. It’s always the model looking down at herself. I was looking for a body I could mistake for you. There was a girl I remembered, but I couldn’t find the sketch. It’s probably hanging in a gallery somewhere.

Maggie never knocks; she walks in. I don’t think she guessed what I was up to. Models forget that nudes have anything to do with sex, and, as I said, Maggie is one of the best. She’s shrunk. All those beautiful swells of flesh have ebbed away. She’s an old balloon. An old lady.

‘You’re up here, then, with the girls. Should have known it.’

I left the paintings and moved over to kiss her and throw an arm over her shoulders. Even standing straight I could have fitted her under my chin. We’ve become perfect dancing partners. It wasn’t long before she shook me off. ‘Enough of that.’ I don’t know when we stopped touching each other, but it was years before I left. They’re odd here, with their rules for children, their rules for young men.

She squinted up at me. ‘Your dad’s sleeping. I got him a blanket from the box. Better get ourselves back downstairs and give him some company. You can show me whether you can make a decent cup of tea after all these years.’

I was glad of the smile.

We had a nice visit, all in all. She bossed me about the kitchen and rearranged the cleaning products I bought the other day in town, sniffing at labels that didn’t meet her standards. It was only as she was leaving that she came out with it. About ‘that business’.

How You See Me

How You See Me